Not to be confused with git rebase and the ability to squash commits locally with interactive rebase, which is a whole other flamewar.

This post is predicated on giving a crap about the git history you and your team produce. If you don't care about good quality git history then you are wrong because git history is an important aspect of your engineering output.

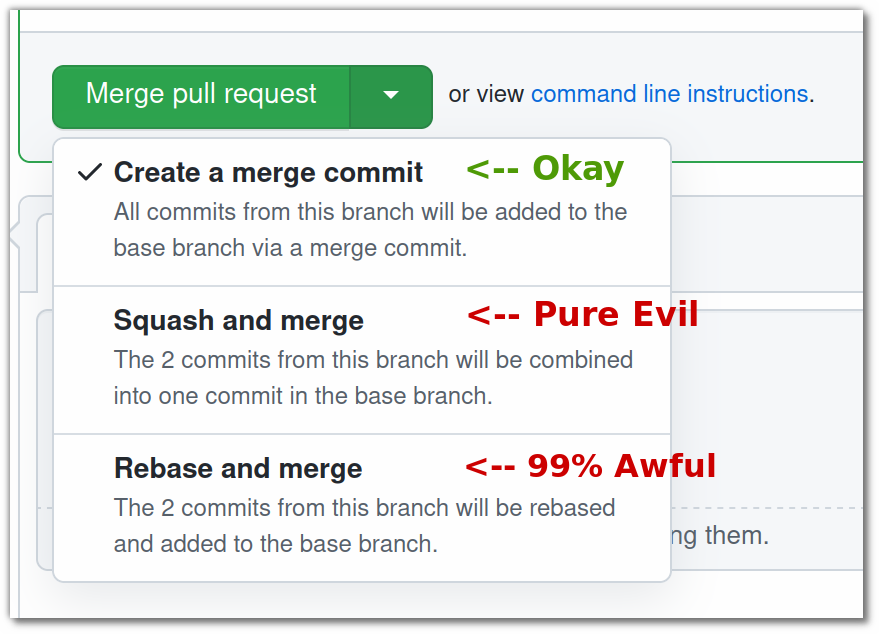

In short, "squash and merge" is never good, "rebase and merge" is almost never good, "create a merge commit" is a good default, ... and if you have a really great team then mainlining while pairing/mobbing can be great for mean-time-to-recovery but shouldn't be the only allowed way.

If you don't believe me yet, then let us now go reaaaally deep on all the details of all the ways you can do this and what makes them so good/bad/evil:

"Rebase/Squash and merge" - both bad

Personally I dislike the "rebase" and "squash" buttons on GitHub because:

- You don't find out what you actually put in

mainuntil after it's done. If you don't believe me check the sha1 of the tip of your PR branch with the new tip ofmain, your sha1 is nowhere to be seen. Github then has the gall to sign the commits as you if you've let it. - There is no record of which commit you based your branch on, so if there's a new incompatibility because

mainhas moved on there is no record of what commit your branch was based on to assist with figuring out where the problem was introduced, it just looks like a bad patch to main with a PR that could never have worked. - The generated commits lose the true commit metadata generated locally (authorship, timestamps, sha-1).

- GitHub generates brand new commit(s) at the point of applying to

mainwith no chance to review first.

These two options behave in ways that are not immediately obvious (to be fair github improved the labels on the options after I first ranted about this, but it doesn't change the fundamental issues). And if you press one of them without realising what it's going to do, tough because it's already in main, and if you have branch protection on (you probably should) then you can't even undo it; it's there foreeeeeeeever.

Someone reviewing your PR has no idea which of these three buttons you will push, which could have been the difference between approving (based on a tidy merge and nice branch history) and rejecting a PR (based on including junk history or a badly worded squash commit).

Let's dive in to the hell that github have created for us:

"Squash and merge" - pure evil

This one takes all your carefully crafted commits (or pile of "wip" junk if you are lazy or plan to squash) and combines them into a single commit, pausing to allow you to write a better commit message (which few people I've worked with bother to actually do, immortalizing "* wip" in the history forever) and then pushing it to main without further opportunity to review what you are shipping.

The behaviour this option encourages, nay, mandates, is to create gigantic 100-file patches that make your eyes bleed to read, basically making git blame useless beyond knowing who to hate.

Anyone who tries to create many small meaningful and logically coherent patches but who has to use this option has the faustian bargain of choosing between making their team review piles of small PRs (too much overhead) or generating one stinking commit in main with all carefully crafted iterations lost to oblivion (for example commit 1: refactor everything, commit 2: make important one-line business change, commit to main: both at once, argh).

Note that github alters your original commit message to retro-fit PR numbers. Also evil.

If you make a change to a file that results in both renaming and modifying files such as a rename-refactor, you can make that easier to follow by doing it in two commits... unless you squash them together. This is exacerbated by git's rename detection which is actually not stored at all, but instead done as a heuristic when viewing patches. If you split the file name change and contents change into two patches you can help a future reader follow what you did, but if you change a file too much and then squash it all together then git will treat it as add and delete, breaking the ability to follow a line of code back through history without even more detective work and guessing.

I have nothing good to say about the "Squash and merge" option. If you don't want to see the messy branches of your developers then use --first-parent. This option in github solves a non-problem and just makes everything worse. Anyone who thinks this option has any merit is wrong.

If an individual developer wants to create a single squashed commit for main they should squash locally and PR that. This option adds precisely nothing to what is possible, encourages reviewing and shipping junk history and encourages bad behaviour and unreadable patches. If you think it annoys me you're right, it should never have been created. It enables shit developers to carry on being shit and generate less "noise" in the history. Why would you want a process that only exists to to take the edge off being around the worst developers?

"Rebase and merge" - 99% awful

This option takes your commits, rebases them on main and then fast-forwards main to the new top commit.

When this option has been used you can no longer tell by looking at the git history that there was ever a PR, which is actually useful context when looking back to work out why the hell something is how it is. (If you look at the commits in github it does magically show the PR number but you can't find that context any other way.)

This option is marginally less offensive to me if used judiciously by skilled teams. You might sensibly use it because your PR was only for peer review rather than because your commits deserve a logical grouping. If you can trust your team to intelligently decide when the commits in a PR would look nice as straight-line history in main then perhaps leave this option available.

If you want your github workflow fool-proof and "scalable" then disable this option. Noobs will find this button and push it for the wrong reasons and give you a shit git history.

The upside of being clever occasionally is outweighed in my experience by the beautiful consistency of everything coming in as "merge PR NNN for feature YYY" and then being able to either ignore the details of the branch with --first-parent (which you can't do if someone has used this button), or look at the commits in that PR as a logical group on the second-parent side when you need more granularity (easily done by running a first-parent log on the last commit of the branch before it was merged).

"Create a merge commit" aka "github flow" - good

My preferred workflow is to use the normal "merge" button every time. This is sometimes know as "GitHub Flow".

In my view you should generate your commits, sha-1 and all, exactly as they will be merged into main, and then as a separate merge commit those should be combined into main.

To avoid many "tramlines" do local rebases to avoid PR branches being based on very outdated main.

- This retains the commit exactly as you crafted it locally.

- It calls out the difference between you writing your commit and deciding it can go into

main. - It retains the information about which commit you based your branch on.

There's something to be said for being able to do a git log --first-parent origin/main and get a consistent list of merged PR branches. It's really quite readable compared to a mishmash of the different styles of merge to main.

You can configure GitHub to disallow the other options if your team are on-board with the idea.

You could argue that single commit PRs are a lot of overhead for something trivial, but equally having to decide each time results in more time worrying about whether something justifies the special treatment of ending up directly on main (in GitHub's modified form), and getting it wrong sometimes.

If your PR branches are full of "wip", "fix tests" and other junk then the answer is not to throw this option out, the answer is to get better at creating good patch sets by learning to use git rebase --interactive and thinking harder about what would make good patch before you start typing in your IDE. (And noticing when your patch is getting messy and stopping to reflect on good patch generation).

I'm aware there are counter-arguments, but in my experience on many teams this seems to end up being the cleanest balance of trade-offs. If you are an individual developer on your own project then pure mainline development can make more sense, though even then thinking of feature branches and having them explicitly merged where appropriate can neatly group related commits. The only compelling argument I've heard against this flow is mean-time-to-fix, but that doesn't mean you have to kill this approach entirely, just be able to use other approaches too.

But my interface can't do first-parent!

Someone once complained at me that we shouldn't do merge commits because they make no sense when viewed in github's deficient history viewer, which shows a random mishmash of mainline and branch commits with no indication of which is which.

Seriously, use a better git viewer, there are literally thousands.

It 100% sucks that github, the flagship platform for git, still to this day does not have a proper branch view let alone first-parent view. Appalling. I'm even more horrified that GitHub desktop has inherited this idiotic denial of branch based views. If the view of history / PRs in github doesn't show you what you need don't use it. Did you know you can review PRs by just pulling down the branch and looking at it locally? You are a capable programmer who uses many tools not an idiot that needs to be spoonfed powerpoint presentations.

Even visual studio can show you branches, merges and first-parent views, it's just a little tricky to find because they insisted on calling everything by different names and using mystery-meat buttons.

Sorry, but I don't have much sympathy with the "my tool is shit so we should do a worse job" complaint against doing things properly, it's weak.

The case against PRs

The only team I have ever come across that (incorrectly) disabled the "create a merge commit" option did so (I believe) in the name of "mean-time-to-recovery". This is however a false dichotomy.

If you want fast "mean time to recovery" (MTTR) you need to be able to ship a patch to main and on to production fast. There is nothing about the ability to create merge commits or use PRs that prevents that. So long as you don't enable the "require a PR" option in github, there's nothing to stop a team pushing straight to main when that's the right thing to do.

I like the idea that the requirement is not a pull request, but just two pairs of eyes on everything. That gives you the ability to be more responsive as pairs can now ship straight to production. That said, I just don't buy the idea of "mainline development" for every patch. Some changes are just more complicated than a single patch and it's good to be able to break things down in a branch before merging. Don't get me wrong, I'm all for pulling groundwork out and mainlining it (if your dev team is good enough to do this) so that your final patch is smaller, but sometimes a feature change has to go in in one commit to main, and without a branch plus a merge commit to main it is just not granular enough to make a useful history. And no, feature flags will not fix this for you, they are a useful thing for sure, and can reduce the size of unmerged branches, but sometimes you just have to change fundamental things that can't be "flagged".

Team culture is worth considering, regardless of tool configuration. If your team does everything by PR then when something is on fire they'll probably raise a PR and then sit around waiting for approval; and if your team always commits everything to main as they go they'll recover fast but their history will be full of mis-steps and fixups that could have been dealt with before they ever hit main. As always extremes are bad and anyone who fast-talks you into believing one extreme is a panacea is glossing over important nuance and interesting counter-examples.

Disabling merge commits doesn't prevent people from having slow PR based async processes, and equally, enabling merge commits and PRs doesn't stop you shipping a quick patch by pushing straight to main when something's on fire. The two things are orthogonal.

The Review part of PR

The existence of a Pull Request implies a review by another developer before merging to main. The series of commits, including their summary, description, author and gpg signature is something that we can review and provide feedback on as part of the review process in order to provide a high quality history for those that need to understand why code is how it is, sometimes years in the future.

I have personally heard many developers say "Don't worry about the crappy history I'm going to squash it". Note the future tense in here. So the reviewer is supposed to just approved the awful "wip" history, or ignore it entirely, and trust that the person that does the merge will pick the right button and generate a sane commit to main.

The branch history in the PR that was reviewed and approved is then thrown away and something completely different goes in to main without any opportunity for the reviewer to object or comment.

What is the point of reviewing something and then committing something completely different to main?

The generated history does have value, should be of good quality, and peer-review is an important part of keeping that quality high.

Perfection?

So what's the ideal? In my view it's the one of the following depending on the quality of your team and what your goals are:

High performing team with top-end developers - reducing mean-time-to-fix

- Two pairs of eyes rule.

- Don't disable anything, just educate and trust

- (... apart from branch protection to avoid force-push to main because forward-only is good)

- (...... and you can probably tell I wouldn't mind if you did disable squash and perhaps rebase given the above ranting).

- Use judgement for when to pair, mainline, PR etc.

- Practice all approaches so that team is used to fast fixes.

Trust your team to use the right tool in the right moment. Big hairy feature? Break it down, use PRs if useful, ship as a merge commit with nice history and link to story and PR. Production on fire? Pair/mob and mainline that sucker.

Mediocre / mixed team, avoiding breakages over fast-fix

- Require PR for all changes.

- Disable everything but "create merge commit".

- Review PRs for quality of commit list and require rewriting branch history till it's up to team standards before merging.